On Muslim YA Novels

I was a bookworm growing up, and so it was easy for me to get lost in the stories I was reading. For a very long time, I was particularly attracted to the ease with which Young Adult literature pulled me in.

As much as I would want to be absorbed into these stories and as well written as they were, they still made me feel like an outsider. My reality was and is very different from that of the blonde white teenage girl who was, more often than not, the main character in the story. And it was more than my tanned skin and hair that is far darker than most YA heroines; my experiences growing up didn’t quite match. While these stories centered on coming of age parties I was struggling with how to wear my hijab while also being fashionable. While the folks in my YA books were experience a blushing first romance, I was trying to reconcile pop culture with the teachings of my conservative Muslim upbringing.

Muslim women are rarely the main characters in literature and stories, and when they are – its usually serious topics, almost always non-fiction. So I ended up reading much heavier books like Jean Sasson’s Princess, which follows the life of a Saudi princess and the way in which she is controlled and oppressed. Not necessarily the stuff one might want to snuggle into a bean bag chair about.. Why was it that Muslim women were always featured in stories that were so sad, so painful and so hard for a 15 year-old Muslim teen girl to digest.

I wanted to read about stories and characters that reflected my own daily life. It wasn’t until last year that I came across two books that completely changed my perception of what I’d always wanted from my favorite Y.A. books. And, now, S.K Ali’s With Love From A To Z , and Uzma Jalaludin’s Hana Khan Carries On have completely changed my own demands from the literature I consume.

As a 22 year old at the beginning of her career in media, Jalaludin’s Hana felt like she was written just for me. She finds unlikely friendships online, rants on anonymous platforms, and navigates issues of family and independence. Jalaludin’s story never once lost its spark. Its focus on humorous themes like Hana’s obsession with poutine biryani, her constant indecision about which hijab to choose (leopard print usually wins) in a way that doesn’t turn Hana into a limited, obvious ‘hijabi’ character, and her own Brown family drama. It’s all fixed in a lighthearted setting, a much needed simple reflection that I wish I’d seen sooner. .

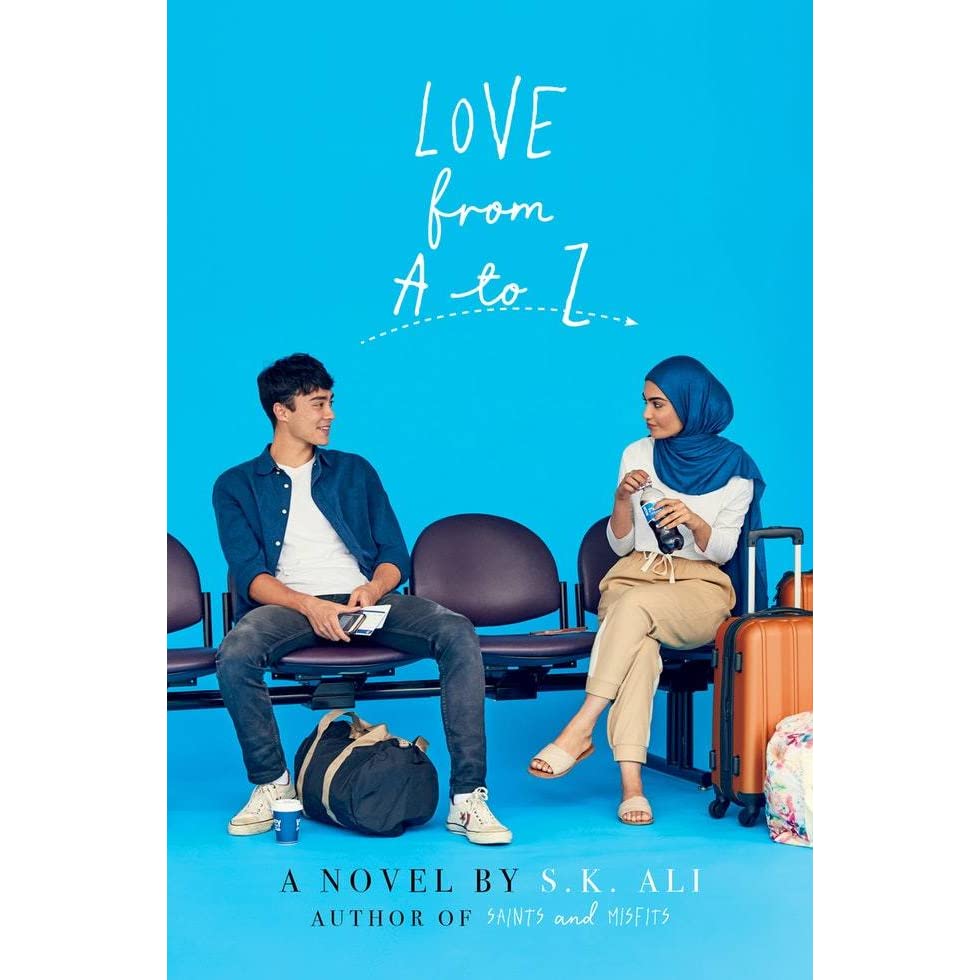

S.K. Ali’s young romance novel is set miles away from Hana’s Toronto. There, Zayneb and Adam – the former of Pakistani Guyanese Trinidadian American background and the latter of Chinese Finnish Canadian ethnicity – meet in Doha, Qatar and navigate a Muslim-friendly romance all while fighting to expose Islamophobia. Zayneb and Adam were the first fictional couple I came across who put their religion and beliefs regarding relationships at the forefront of their budding romance. Yet despite its obvious presence, their religious identity never feels like it’s falling into overused, cliched character territory. Indeed, Ali’s novel actually deals with overdone issues like the hijab and Islamophobia in media in new and fresh ways that were far more relatable to my own everyday experiences as a Muslim woman.

In reading both of these books, I found myself drawn to two Muslim female protagonists who allowed me to connect with a major fictional character in a way I’d never before felt. . Not that to say I haven’t read any other books on Muslim women – in fact Fatima Mirza’s A Place For Us remains one of my favourites – but Hana and Zayneb sparked a certain joy inside of me – ne that came from seeing two Muslim women who were strong without being sad, naturally funny, and pretty much just like your average chick-lit heroine aside from everything that made them uniquely Muslim.

As a journalist myself I was particularly intrigued by Hana, her podcast and her wish to have her own radio show. I found her choices reflected in my own decision to start a publication where I could highlight my own local stories and in wanting to be a journalist in order to take control of the narrative. When she stood up to her producer for stereotyping media coverage of Muslims in the name of representation, I realized just how badly I wanted to be like her. Maybe if Hana and I had met when I was still searching for my own career, I’d be less accepting of the crumbs I’ve thus far seen as a poor stand-in for representation. Maybe if at 16 I’d come across the likes of Zayneb, I’d feel a lot less torn between having to choose between my religion and the rest of my life.