In pursuit of Wagd: How lurking near the fringes of ‘peripheral’ Sufism led me towards appreciating the heart of Islam

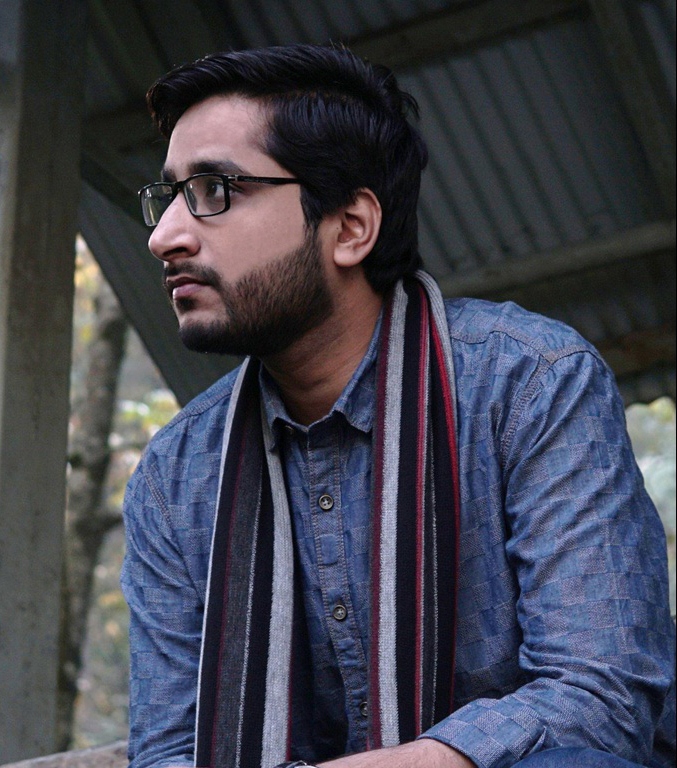

They call Muhammad Samie the spell caster. Samie is 32 years old, and he has a background in chartered accounting. He is also a rising qawwali singer, lest you think that the square-framed glasses that rest on his nose speak to anything else. His work is the spiritual music of South Asia that is rooted in Sufism, Islamic mysticism, and oneness with love, music and God and appeals to a universal audience, crossing borders almost as nimbly as Rumi himself.

They call Muhammad Samie the spell caster. Samie is 32 years old, and he has a background in chartered accounting. He is also a rising qawwali singer, lest you think that the square-framed glasses that rest on his nose speak to anything else. His work is the spiritual music of South Asia that is rooted in Sufism, Islamic mysticism, and oneness with love, music and God and appeals to a universal audience, crossing borders almost as nimbly as Rumi himself.

The word qawwali itself stems from the Arabic root word qaul (to speak), alluding to the format’s use as a “vehicle” delivering the Sufi message: to constantly cultivate the inner self rather than ritualistic practice and demonstrate obedience to Him stemming from love, not fear.

Traditionally in qawwali, the Sufi message, called the kalam, is accompanied by instrumental preludes, melodic scale-like vocalizations and tonal improvised melodies serving as undercurrents to establish the hypnotic rhythm of clapping patterns. Thanks to its almost cult-like following, the experience of listening to a qawwali is aimed toward rhapsody, complete with the objective of pursuing a sort of otherworldly wagd or religious ecstasy. But flamboyant displays of vocal skill, such as jugalbandi (literally entwined twins or a duet, almost like a “face-off” between two singers) historically take up much of the musical—and mental—space.

“I was always entranced by qawwali,” said Samie, “But when I’d sit down to enjoy the words and the poetry itself, I was faced with such elaborate displays of vocal dexterity instead that it was frustrating.”

As a 21st century qawwal, Samie sought to make the ancient music genre of qawwali more accessible for his generation. So he’s on YouTube, where his eponymous channel features a collection of Short Sufi Spells, which hinge as much on the word Sufi as they do on the word short. By removing the long musical or vocal interludes, the listener achieves a state of wagd more quickly—in seven to 12 minutes instead of up to an hour. Wagd as a spiritual state isn’t always a guaranteed outcome, and is experienced in unique ways by different people. Usually, however, it’s defined by a trance-like state, with some listeners preferring to turn inwards, and others feeling an irrepressible urge to sway, clap, dance or whirl. The Sufi message of love takes over, and there is an intense feeling of union, harmony and inner peace .In an age of listicles and twaikus, Samie is the living culture of the Sufis and their magic.

The more famous qawwals are born into the legacy of a literal qawwal dynasty,a gharaana or family lineage where the craft is passed on from generation to generation via an intense training in classical music under an experienced Ustaad. (Amjad Sabri and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, the latter of whom spent time crossing over with the likes of Peter Gabriel and Eddie Vedder.)

Samie found his way into the world of devotional music on his own. His journey started when he received a piano in his college hostel as a gift. With members of the more orthodox Islamic political parties also in residence, Samie recalls closing the doors and playing gently for fear of being caught.

“Just as a native speaker of English doesn’t consciously construct the present perfect tense while speaking, I don’t know the notes,” he said in an interview. “It’s just a remnant … a translation of the intensity of our feelings … be it ecstasy or angst. There’s no ‘me’ or ‘I.’”

Contrary to the general understanding of Sufi asceticism as completely removed from worldly concerns, this life isn’t ignored in favor of the afterlife. Samie’s most popular Spell, Maikada (which means pub) is steeped in opulent wine-related imagery (metaphorical and otherworldly wine, of course, as consuming alcohol is forbidden in Islam). It has over 14 million YouTube views. In another work, Samie reflects on the ill-fated, centuries-old love affair between the moth and the lamp: “Maybe the joy of living is in burning,” he sings. Verging on such “dangerous” territory by fundamentalist standards requires treading cautiously to avoid misinterpretation, and perhaps that’s why each of his Spells is preceded by both a disclaimer and a bold, red warning, advising viewers and listeners to “interpret with caution and at their own risk.”

And perhaps that’s the very danger that drew me to his work. For me, the spell caster, and the entire ethos he embodies, helped resuscitate my spluttering faith. The closer I came to the geographic core of my religion in the Republic of Pakistan, the more disenchanted with it I became.

In that sense, California proved a safer harbour for my faith than a Pakistani metropolis. In my 95616 zip code, where I grew up, I knew an Allah that was merciful, benevolent and kind, loving me with the force of 70 mothers. My Allah said things like, “‘Be’, and it is.” And just like his command, my faith just was. Fed by beautiful narratives woven at bedtime and lessons that shone in the purity of their intention—though hazy in their cross-references to fundamental texts—I flourished in the “indirect light” of faith.

In that sense, California proved a safer harbour for my faith than a Pakistani metropolis. In my 95616 zip code, where I grew up, I knew an Allah that was merciful, benevolent and kind, loving me with the force of 70 mothers. My Allah said things like, “‘Be’, and it is.” And just like his command, my faith just was. Fed by beautiful narratives woven at bedtime and lessons that shone in the purity of their intention—though hazy in their cross-references to fundamental texts—I flourished in the “indirect light” of faith.

All that changed when I moved to Karachi, Pakistan. My aunt told me Allah would cut off my finger-tips if they reached past my knees while I prayed. The devil would eat from my plate if I inadvertently forgot to say Bismillah. Hadn’t I heard of the girl who turned into a monkey for disrespecting the Quran? Making a bun on my head meant I’d be bereft even of the scent of paradise, and if I drank water while standing up, it would be so monstrous that I’d vomit it out—if only I knew.

If only.

With time, the warm embrace of Islam started to feel like a noose. I recoiled, becoming an outcast in my own “homeland” until slowly, by imperceptible increments, I found my heart thawing in the symbolic wine of my metaphorical Maikada. Reserved mainly for male devotees or elaborate communal qawwali troupe nights, my forays into asceticism didn’t follow the conventional path, and it is unlikely that I would have had the same experience without short sufi spells I could enjoy in the privacy of my own home—quickly. Samie’s work, serving as a gateway to other classical qawwali and devotional music, reversed my disenchantment, partially because it shone with immediacy and themes I wanted to relate to.

While Sufism is sometimes regarded as “periphery,” ranking “lower,” almost, than the core tenets of Islam, when looking in from the fringes of mysticism, Allah becomes more accessible. That’s one of the markers of Sufi music that made it so inviting to me. I felt as if I could participate in a conversation with God. Even the use of pronouns belying familiarity, (“tu,” “tum,” and “aap” all mean “you,” but “aap” is reserved for elders and is used out of respect, whereas “tum” is used when speaking to someone younger, and “tu” is the most familiar and colloquial of all) cut across the distance.

For example, a popular qawwali written by Baba Fareed and performed by the iconic Pathanay Khan begins with the words, “Mera ishq vi tu, mera yaar vi tu”, (You’re my ardour, my friend). “You’re my Mecca … my pulpit … my Quran,” he continues. But as the song reaches its climax, such consecrated imagery gives way to expressing love for Him through objects close to the qawwal’s heart: “You’re my henna … my rogue … my tobacco, my betel-leaf!”

Qawwali doesn’t place divinity on an unattainable pedestal. Like the parable of Moses and a “sweetly blasphemous” shepherd’s prayer (“My beloved God … I would wash Thy feet and clean Thine ears and pick Thy lice for Thee. That is how much I love Thee”) in The 40 Rules of Love, Sufism doesn’t hinge on having all the right answers, but rather having the right intentions and speaking to the Creator in the way we flawed humans know best.

It’s a powerful feeling of union and one I was denied when I moved. The types of frivolous things we, as Muslims, can get caught up in while ignoring the core principles of Islam is phenomenal, really. Our discourse is viewed as theologically saturated—and at times, it is. And the basic current of love for Allah seems to get lost in translation. Just listen to the call-in segments in Islamic television shows and the banality of the questions is absurd. “Should we call it Ramadan, or Mah-e-Ramadan (the month of Ramadan)? What happens if my child is left-handed and can’t eat with his left hand?” There are bizarre questions and, somewhat more surprisingly, elaborate answers for each. And unfortunately, with the self-appointed guardians of faith, there is only one right option.

Not so with qawwali. In one of my favorite Spells, Samie laments that he is bereft of Allah’s venerable doorway as a place of worship, but then consoles himself with the fact that our job is to prostrate—whether at home or at the world’s most prolific religious sites. Because sometimes, good enough really is good enough, and religion isn’t bound—not by ritual, and not by geography or tradition, either.

Today, much like American gospels, qawwali has spawned a pop genre. But Samie’s work isn’t a dupe. It’s a distillation. Drawing upon the entire canon of classical Urdu poets, such as Mirza Ghalib, Allama Iqbal, Jigar Muradabadi, and Josh Malihabadi, among others, and continuing the tradition of eminent qawwals, his work is laden with literary allusions. He describes the process as “girha lagana” (making knots) on a loom that has been in the process of weaving a beautiful tapestry since time immemorial. The final image remains shrouded in mystery, but the essence becomes marginally clearer with each artist who makes more knots and each listener who gets lost in the trance. In a way, when the final culmination of the “tapestry” washes over you and you are dazzled by the power of Ishq-e-Haqeeqi (the “real” love or love for Allah), it leads to the listener somehow finding themself.

For me, Samie’s short Sufi spells have truly become my fast-track to religious ecstasy—through a route circumnavigating dismembered fingers and devil-shared platters and resplendent, instead, in hope of union with the ultimate beloved: Allah. They’ve been my shortcut in a pursuit of wagd.