Dialogue: Malachi 3:3

Hi, I’m Elizabeth*, and I’m a Unitarian Universalist from New England.

Hi, I’m Elizabeth*, and I’m a Unitarian Universalist from New England.

Hi! I’m Stephanie, and I’m a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints living in California.

We’ve been friends for more than a decade. We were both raised in our faith traditions and decided to stick with them as adults, and we’ve spent a lot of time talking about faith and comparing our beliefs. While our churches are wildly different in some ways, we always seem to come back to some core agreement when we talk about faith.

But in this space we’re doing something new: We’re going to come to some mutual understanding about a Bible verse.

It’s an inherently uneven conversation. While Elizabeth did attend Sunday school as a child, she can’t recall a single class about the Bible. There must have been something, but she can’t remember it. Her greatest exposure to the Bible comes from listening to Georg Friederich Händel’s Messiah on repeat every Christmas season for more than 20 years. The Messiah tells the story of Christ through a selection of Bible verses put to music. She’s memorized most of it but rarely looked up any of the words in the actual Bible.

Stephanie, on the other hand, has been reading the Bible since she was a child. In high school, she started attending intensive scripture study classes at church, reading one book per year in this order: the Old Testament, the New Testament, the Book of Mormon, and the Doctrine and Covenants. Those last two are foundational texts in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Since then she’s taken more than 30 courses on specific topics within all four books. In other words, she has committed a significant amount of time to scripture.

In an attempt to make this a fair conversation, Elizabeth selected three lines from Handel’s Messiah, and then Stephanie picked one of them. So here we go:

“And He shall purify the sons of Levi, that they may offer unto the Lord an offering in righteousness.” (Malachi 3:3)

Watch the excerpt from the Messiah to hear the verse put to music:

Elizabeth was excited to dig into a question she’s had for two decades: What did the sons of Levi do so wrong that they needed to be purified? And this is where we reached our first conversational crossroads: The sons of Levi did not do anything wrong. It was just the opposite.

Stephanie: I love this starting point. It’s so interesting to have a conversation where someone says, “Whoa, I thought it was the other way around,” and also a person saying, “Where do we go from here?!”

Elizabeth: (Laughing.) So wait, what actually happened?

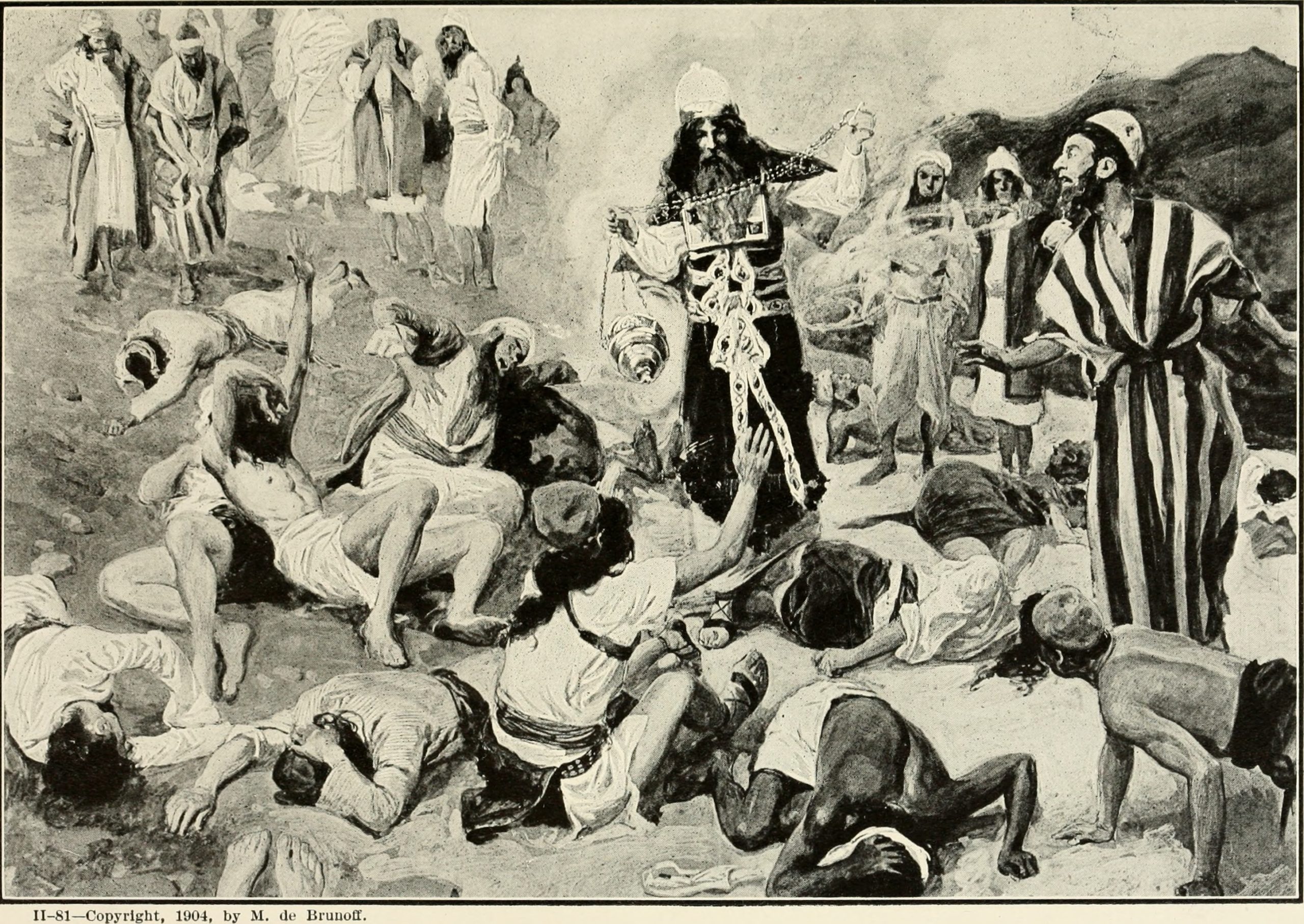

Stephanie: This goes back to Moses. Moses went to the Pharaoh and said, “Let my people go,” because his people were enslaved. Pharaoh denied that request. So, God sent Pharaoh a series of plagues, including locusts, frogs, and darkness. But Pharaoh wouldn’t budge. Then God sent a plague that killed the firstborn child of every house—except Moses’s people, the Israelites, were spared.

Moses’s people left Egypt, and they organized themselves into 12 tribes, named after the 12 sons of Jacob. These are referred to as the “twelve tribes of Israel.”

Elizabeth: Some of this is ringing a bell. But who is Levi?

Stephanie: Levi is one of the 12 sons of Jacob.

Elizabeth: Oh!

Stephanie: In the religious tradition of that time, the firstborn son of the family had specific duties. Under the law of Moses, the firstborn son belongs to God: “All that openeth the matrix is mine” (Exodus 34:19). However, when Moses’ people arrive in the wilderness, the Lord, through Moses, assigns priestly duties to the entire tribe of Levi. The Levites act as a substitute for the firstborn.

Elizabeth: I’m following you.

Stephanie: Before we got on the phone, I looked up more information on the role of the sons of Levi. I found in Numbers Chapter 8 (in the Old Testament) that the Lord tells Moses that he wants the tribe of Levi to serve a priestly duty, and they need to be purified through a ritual to get ready for this role.

Elizabeth: So the sons of Levi are being chosen to be priests for the whole group, and that’s why they’re getting purified through a ritual?

Stephanie: Yes!

Elizabeth: But the tune of the song is so upbeat, it sounds like good news! I’ve always assumed the good news is that some bad guys are going to get a second chance by being purified.

Stephanie: I can definitely see how you came to that conclusion!

So here’s a different question: The Israelites were already God’s chosen, the ones whose firstborns were spared in the first place. If they were already a people who followed God, why did they need to be purified? How is being pure more than simply being a good or believing person?

Elizabeth: Those are great questions. I wish I’d spend 20 years pondering these instead! To be honest, though, I have some trouble with the idea that one group can be more pure than another based on a ritual, or that priests and ministers are more pure than everyone else.

Stephanie: I would agree that priests and ministers are not perfect or more important than anyone else, as we are all created equal. So, why the special purification ritual for them?

Elizabeth: Maybe it’s because they have this new role? Anyone wants a good start to a new job. It sounds like the sons of Levi have a new job. Unitarians have a belief that everyone is born with gifts to offer the world and that you can help others nurture their gifts, and you can try your best to know your own gifts.

So the sons of Levi—well, I’m doubtful that all of them have this same gift for the priesthood. Surely at least one of them wants to be a dentist.

Stephanie: That’s a great point. How can an entire tribe of people have the same job? As I listened to your description of gifts, because we all are unique, I thought about how the priesthood works in my faith. I believe that the same priesthood that existed with the Levites exists today. The priests in my church don’t get paid and have their own jobs out in the world to provide for their families: They are dentists, lawyers, landscapers, and so on. In addition to their day jobs, these individuals also spend a lot of time serving in priesthood duties.

Elizabeth: That’s so interesting. This point about the gifts—one thing I’d say is that a person’s job doesn’t have to represent their gift. Sometimes it does, but anyone’s gift can be separate from income, you know what I mean?

So I’m thinking, with the sons of Levi, is the purification more about the larger community? It seems like, OK: We have 12 tribes, and one of the tribes is going to be priests. Maybe it’s less about each individual son of Levi and more about the collective and their role for the bigger group. Am I way off base here?

Stephanie: I think you’re right. The tribe was offered to the Lord as a group offering on behalf of Moses’s people. And for us to offer anything to the Lord, it has to be pure. Therefore, if the Levites were the offering, they needed to be purified. There’s a scripture and I’m going to try to find it for you. … Here it is. Omni 1:26 in the Book of Mormon: “And now, my beloved brethren, I would that ye should come unto Christ, who is the Holy One of Israel, and partake of his salvation, and the power of his redemption. Yea, come unto him, and offer your whole souls as an offering unto him.” This applies to all of us—if I offer my whole soul to God, I need to be purified too. I need to repent and take out of my heart the desire to sin so that what is left is a pure heart.

My question for you is, what does it mean in your faith to be pure?

Elizabeth: Purity in Unitarianism? Well let’s see. Many Unitarians don’t believe in God (and might even ask me to downcase that—god). And then a number are agnostic, and then some believe in God but maybe not the Bible, and then we get into personal theologies…

But there is a clear concept of community in Unitarianism, and it’s really about creating a just world in the present. The word “pure” might not resonate with a lot of Unitarians. But the idea that a group of people are here to serve the community—that would make sense. It’s just that the average Unitarian might do that by, say, registering people to vote, with the idea that equal voting access makes for a more just society, or marching for environmental justice. Something like that.

Stephanie: If a Unitarian were to give a gift to God, not a specific gift, but any gift in general, how would you describe that gift? What should be the condition of that gift?

Elizabeth: I think many Unitarians would probably not consider it a gift to God. But setting that issue aside: The main point would be that the gift makes the world a better place right now. If a group of Unitarians see an injustice, they’re likely to plan a strategy to seek justice, and that group might be like a temporary “Sons of Levi” tribe. But how do they get pure? Maybe through a lot of conversation and thought about what they’re doing and why, and whether it will help, and some prayers.

I’m a bit out of my league, because I never participate in this part of Unitarianism! I never march for any cause, or sign up for these group efforts.

If I answer your question on a personal level: Say I want to use one of my natural gifts (and we all have gifts) to create something that I hope will make the world a bit better. I would have to offer the very best of myself, with no eye toward my own glory, but rather the common good. Then my offering could be “pure.” Or “an offering in righteousness,” like the song says.

And you know, I guess that’s a version of the scripture you brought up, and what you mentioned about offering your “whole soul” to God.

Stephanie: And I think that’s the point. Anyone when taking on a role in this world should do so with a pure heart.

Elizabeth is a pseudonym. We are only using Stephanie’s first name.