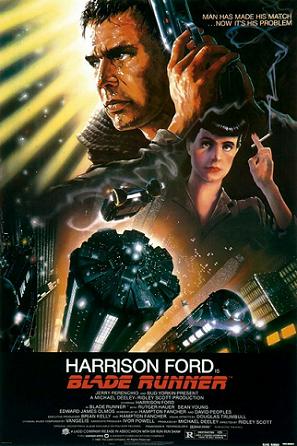

I want more life, fucker: The parable of Roy’s dove

For three guys who attended a daily chapel service every morning before high school, the religious imagery during the climactic scenes of Blade Runner might have felt a little too overt. I’d seen the movie for the first time at the Angelika Film Center in New York City – a late-night showing of the director’s cut more than a decade after the movie had put its indelible mark on sci-fi – along with a couple friends from Lancaster Mennonite High School. Years earlier, before we’d graduated and moved on, we absorbed our fair share of religious symbolism. Although we all loved the movie – for me, it remains a favorite – I felt myself cringing a bit when the dying replicant Roy Batty sticks a nail through his failing hand to revitalize it. The nod to Christ’s crucifixion wasn’t especially subtle, mind you.

For three guys who attended a daily chapel service every morning before high school, the religious imagery during the climactic scenes of Blade Runner might have felt a little too overt. I’d seen the movie for the first time at the Angelika Film Center in New York City – a late-night showing of the director’s cut more than a decade after the movie had put its indelible mark on sci-fi – along with a couple friends from Lancaster Mennonite High School. Years earlier, before we’d graduated and moved on, we absorbed our fair share of religious symbolism. Although we all loved the movie – for me, it remains a favorite – I felt myself cringing a bit when the dying replicant Roy Batty sticks a nail through his failing hand to revitalize it. The nod to Christ’s crucifixion wasn’t especially subtle, mind you.

Yet, those scenes remain indelibly lodged in my memory. The superhuman Roy, having turned the tables on the man sent to kill him, chases his tormentor through an abandoned and decaying apartment building. And, as they climb through the building and out onto a small ledge above the dystopian streets below, the film’s intriguing questions about what it means to truly live take on increasingly spiritual overtones. They sit on the ledge in the pouring rain and, as he reaches the end of his lifespan, Roy releases the white dove he’s embracing into the heavens. Now, decades later, while writing, editing and contributing to works about artificial intelligence, data and related technology issues, that’s the scene my mind regularly returns to when thinking about the far reaches of AI’s theoretical potential. The replicant Roy, a being of artificial intelligence and manufactured body, reaching the end of his lifespan and waging a furious but fruitless attempt to extend his time, is entirely clear about what he’s fighting for. Like he says earlier in the film: “I want more life, fucker.” One wonders here how much meaning Roy packs into “more life” – a longer life span, sure. But is he also demanding the fullness of life that goes beyond implanted memories, deep intelligence, and hyper-strength to something more profound, more spiritual? It all comes back in Roy’s final scene, where his symbolic life force – or his soul, or his spirit – flies away, rising above the city that would deny him any humanity.

Overt metaphor aside, Blade Runner, and that scene, remains a primary reference point when I imagine the future of AI and humanity. First things first, though: Despite a steady stream of impressive AI advances and demonstrations, current versions of these technologies are still considered “narrow.” Although they might operate at a super-human level on the specific tasks for which they’re trained, they can’t apply that capability to another problem unless they’re re-programmed. The same system that beats the world’s grandmasters at chess would be hopelessly lost in a child’s game of checkers. The conception of artificial intelligence or super-intelligence we often see reflected on the screen or on the page – AI that can generalize across different domains, as can humans – lies years and multiple major breakthroughs ahead.

But then again, we never needed one of the Tyrell Corporatins’s “more human than human” replicants to imagine some sort of spiritual continuum for non-human entities that display intelligence, did we? When researchers discovered that brainless slime molds display a basic collective intelligence that lets them navigate mazes, the story was remarkable enough to jump from scholarly journals to mainstream headlines. While I’m inclined to believe that I contain greater intelligence than the slime mold, I’m also not quite willing to accept this as a simple hierarchy. As Wired founding editor Kevin Kelly once suggested, “There is no ladder of intelligence. Intelligence is not a single dimension. It is a complex of many types and modes of cognition, each one a continuum.”

What I haven’t yet fully justified, though, are the hierarchies I still draw between intelligence and spirituality. It blurs some distinctions to do so, but my mind still runs a strand through intelligence, to consciousness, to moral standing, and then to spirituality. I find nothing exceptional about consciousness, at least not in humans, and I can easily accept the idea that a generally intelligent AI could possess as much. From there, I think back to an interview with New York University philosopher David Chalmers. In that interview, Chalmers noted that a conscious being is both a moral agent and a moral patient – able to decide what is moral but also deserving of moral treatment by others.

As the son of a Mennonite preacher and scholar, I’m hardwired to believe that humans possess a certain spiritual exceptionalism that’s tied at least partly to intelligence and/or consciousness. The basic tenet of Mennonite and other Anabaptist faiths dictates that one must choose to be baptized and join the church, a split from the Catholic Church’s infant baptism. When a person believes and is baptized, God imbues us with the Holy Spirit. Still, I cannot accept the Holy Ghost as the sum of spirituality, which I see as far more multidimensional and embodied not just in humans or other living organisms, but potentially in artificial beings as well.

I don’t know if or how we ultimately jump from the recognition of moral agency for conscious artificial beings to the actual consideration of a soul or a spirit in that same being. It certainly feels a lot easier to grant spirituality and moral agency to things that more closely resemble ourselves. Consider, for example, the ongoing conversations about robot rights, with researchers and policymakers debating whether artificially intelligent systems will remain mere tools or, at some point, become something more. We humans can justify all kinds of morally outrageous ideas, but most people would agree that keeping a generally intelligent humanoid as a slave would pose a greater moral conundrum than packing up Sophia and taking “her” to South by Southwest 2022.

But if intelligence, consciousness and moral agency aren’t reserved solely for entities that emerge from human DNA, why should spirituality be? I take it on faith that other people can or do occasionally experience profound epiphanies – ethereal moments when we sense something bigger than ourselves. At what point do we take the same leap of faith for non-human beings? At what point could we believe that the replicant Roy released a metaphorical soul at the end of Blade Runner?

I’m not sure I’ll ever have an answer, but I increasingly wonder if it’s the right question to ask. Perhaps, rather than wondering whether the machines themselves can contain a spirit, we might use the AI technologies we already possess in search of a whole new spectrum of epiphany. Long term, for example, we might use AI and brain-computer interfaces to capture more information about spiritually revelatory moments – a sense of a higher presence – and analyze those previously unquantifiable experiences. More immediately, we can take the extremely complex pattern analyses and predictive power that AI systems already possess and use it to open our eyes to new phenomena – methods to combat climate change or develop personalized medicines – that make us stop and reconsider the universe in which we live.

That might not be good enough to satisfy the replicants’ demands in Blade Runner, at least for now, but it might also help us understand a little bit more about our own humanity. Maybe then, when some future Roy says he wants more life, fucker, we’ll do better than sending a blade runner to hunt him down.