Learning Hebrew to Sing

I can’t converse in Hebrew. I can’t hear it speak back to me in my own voice. I can’t even fumble with words and phrases like I’m learning the language for the first time. The survival of the Jewish people — and therefore the Jewish tradition — is in and of itself a tenant of contemporary and historical Jewish life. This was never more true than in the second half of the 20th century. So like so many other children of children who survived the Holocaust, I can only sing — not converse in — my native tongue.

I can’t converse in Hebrew. I can’t hear it speak back to me in my own voice. I can’t even fumble with words and phrases like I’m learning the language for the first time. The survival of the Jewish people — and therefore the Jewish tradition — is in and of itself a tenant of contemporary and historical Jewish life. This was never more true than in the second half of the 20th century. So like so many other children of children who survived the Holocaust, I can only sing — not converse in — my native tongue.

This tenacity — and I’d argue that tenacity, and perhaps then also guilt, are pillars of contemporary Jewish thought and experience — produced a rather half-hearted result: Hebrew came to me via a handed-down, abridged, version of Judaism. That is to say the goal of my Hebrew education was not fluency. It was, instead, a more perfunctory Hebrew set of lessons that pointed me toward my Bat Mitzvah.

I spent each Monday and Wednesday from kindergarten to eighth grade in a Reformed temple that sat on a wooded street on the outskirts of a particular Jewish suburban commuter town, learning a language I was not expected to understand. We would board the bus from the middle school and flirt or bicker on the way to the temple. We would eat bagels for an hour in the lobby, bartering for vending machine candy with promises of completing other’s homework. We would quickly do the Hebrew homework assigned last week as the Rabbi called us into the main congregating space and reminded us that we were the representatives of our faith, and so we would carry Judaism to the future. We passed notes under the seats.

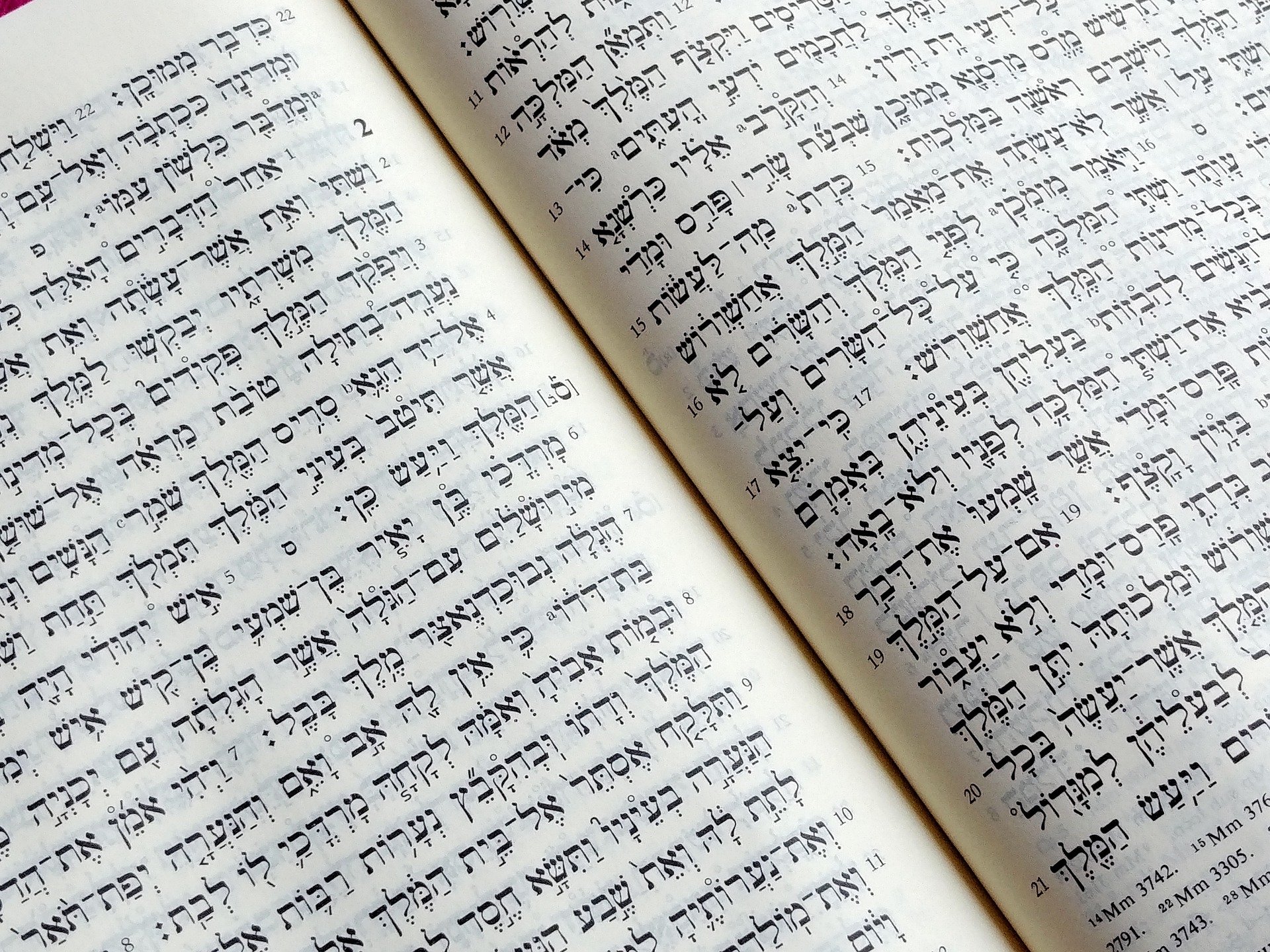

Despite it all, I came of age here. When I turned 11, I began one-on-one lessons with a cantor whose hair was cut like a bowl turned upside down. She would draw arrows over the Hebrew I would sing on my Bat Mitzvah day so I would know what tone each word was. I memorized these tones — not the words; the tones — practicing each night for months. I would make my mom listen to me as I traced the arrows — and not the Hebrew — with my fingers. Despite the few hours I spent learning the meaning of my Torah portion, the actual Hebrew words quickly lost their meaning to me. The Hebrew was only a visual cue for a sound.

I was rather preoccupied with the guest list for my Bat Mitzvah party, the true pinnacle of the American Reformed Jewish experience. The event was not ever going to measure up to the absurdly exorbitant parties of my peers (think: pillows with the bat mitzvah’s face on it, custom snuggies, ice cream bars and free sweatshirts and photo booths and danceteurages and choreographed entrances and special appearances and games and back-up dancers and an open bar for the parents and a whole lot of nouveau-riche cash thrown at the ultimate sign of having made it, having finally assimilated, of having achieved the American dream). My family never fit into that world — I certainly didn’t, and that would eventually make for some tension. But at 12, I hadn’t figured that out yet. I was desperate to be like my friend. Anyway, this mattered. Learning Hebrew did not.

My Torah portion was, rather disappointingly, about curing meat. I was furious. The time of day that a sheep can be killed really meant nothing to me. The passage felt irrelevant. What could we — what could I — possibly learn from something so obsolete?

I memorized the sounds of the V’ahavta and the Mi Chamocha. I purchased my first training bra. I starred as the Cat in the Hat in “Seussical The Musical.” I picked out a ridiculously bedazzled dress to wear at the reception after my bat mitzvah. I kept wondering how I could possibly make a portion about ancient butchering practice relevant.

Tradition is finicky. I get the value of apples and honey, in the stories (so many stories) of repeated cycles of liberation and oppression, in the raising of toes and bowing of heads during Kedushah. I also find value in the snickering side conversations during Hebrew school, in the smell of my mother, having just showered and liberally perfumed herself, next to me in temple as she leans on my arm, in salami and eggs on Sunday mornings, in Passover meals in uncomfortable chairs and High Holiday services during which I nearly fall asleep, in the feeling of home I grasped immediately after going to a new temple at a time when I felt particularly alone.

But when I read the words of a language I cannot understand in an attempt to comprehend the importance of banal rituals and rules that are outlandishly antiquated, I don’t understand tradition. Just like I won’t accept that my mother wasn’t allowed to be a Bat Mitzvah while my father could be a Bar Mitzvah.

Years after my Bat Mitzvah, my father found a recording of himself singing Hebrew. When my brother and I first heard it, we couldn’t stop laughing. We were surprised to hear my father’s voice with a distinct New York accent. (He claims he trained himself to get rid of it.)

But there was something else in that recording that I couldn’t shake. I could hear — see — my father practicing Hebrew. If I closed my eyes hard enough and held the sound in my mind, that sound that sung to me and tasted like lemons and honey, I could see him at a desk, shoulders hunched, pointer finger hovering over the holy swirls of Hebrew. In the folds of words my father and I existed in parallel. I began to understand more truthfully that there is also a dream woven into the tapestry of Jewish tradition; to pass on something beyond the self; to create continuity where it might not otherwise exist; maybe even to allow space for meaning to erupt from the mundane.

I imagined a xylophone expanding; at each layer was someone I did not know speaking words that may or may not have had meaning to them. These words are the container for a song. Each fold of the xylophone stretches deeper into history, deeper into oppression and resilience and hunger and power and joy and sorrow and maybe even meat curing. There is no way to recognize someone on the other side of the fold, yet, their presence permeates through the instrument, their sound layers upon my own voice. Learning Hebrew only to sing, albeit a flawed scheme in many ways, brings its own sort of sad beauty. The language is serving as a container for meaning.

I can feel this looking back on a moment from my Bat Mitzvah. I am standing on the bimah, about to recite the prayer that will allow me to open the arc and remove the Torah. My mother and father and brother and aunts and uncles sit across from me with the rest of the congregation. I am unsure of myself. I am sweaty and prepubescent and rather preoccupied with not falling in the kitten heels I insist on wearing on this day (there’s my version of womanhood). I’m toying with the seam of my dress as I prepare to sing some words about drying sheep.

I can feel this looking back on a moment from my Bat Mitzvah. I am standing on the bimah, about to recite the prayer that will allow me to open the arc and remove the Torah. My mother and father and brother and aunts and uncles sit across from me with the rest of the congregation. I am unsure of myself. I am sweaty and prepubescent and rather preoccupied with not falling in the kitten heels I insist on wearing on this day (there’s my version of womanhood). I’m toying with the seam of my dress as I prepare to sing some words about drying sheep.

But at this exact moment, an impossible amount of light enters the temple. I know, sounds like a suspiciously drained schtick. But this light is preposterous, indulgent, practically divine. This goddamn light is blinding people! A great uncle who has fallen asleep suddenly jerks awake. Everyone is looking up at the floating dust that is arguably glowing as it weaves through the rafters.

And I feel like a container. I feel filled up. I don’t feel 13. I don’t care that my speech outlining the connection between skinning animals and the current presidency will fail to move the crowd. I don’t care that I will be a woman. I am full. I am full of something that permeates, that is old. I am full of something that has always been there, but that has no immediate meaning.

It’s this fullness that sits in the deep part of my belly long past the shifting of the sky and the chanting of ancient prayers. Words can sing without definition. This much is clear to me.