How to become a confused-ass Muslim

My wife learned the hard way that I lead a double life.

My wife learned the hard way that I lead a double life.

The day we got married, my whole extended family came over for dinner. We’re Muslim, so at sunset, we all lined up for the evening prayer. She’s not, so she stayed at the table.

I queued up with the family and prayed. When I looked up, my wife had turned pale, her eyes red and fighting back tears.

I got her into the hallway where she sobbed, “Who are you?” She knew me as an atheist with a spiritual side, but she’d never seen me pray. Now she could see there was this stranger, nurtured in a very different culture, within me. She was shaking. Needed a shot of whiskey to calm down.

That day I came face to face with something I’d never really understood about my inner life.

As a Muslim American, I’m totally accustomed to a dual spiritual existence: one around my family of believers, and one in private, where I’m as torn up as anybody.

Perhaps that seems phony. Not to me. It’s an adaptation to how I grew up.

When my family gets together, you can see that we’re close. We’re a merry band of hooligans constantly joshing and ribbing and cracking very, very bad potty jokes.

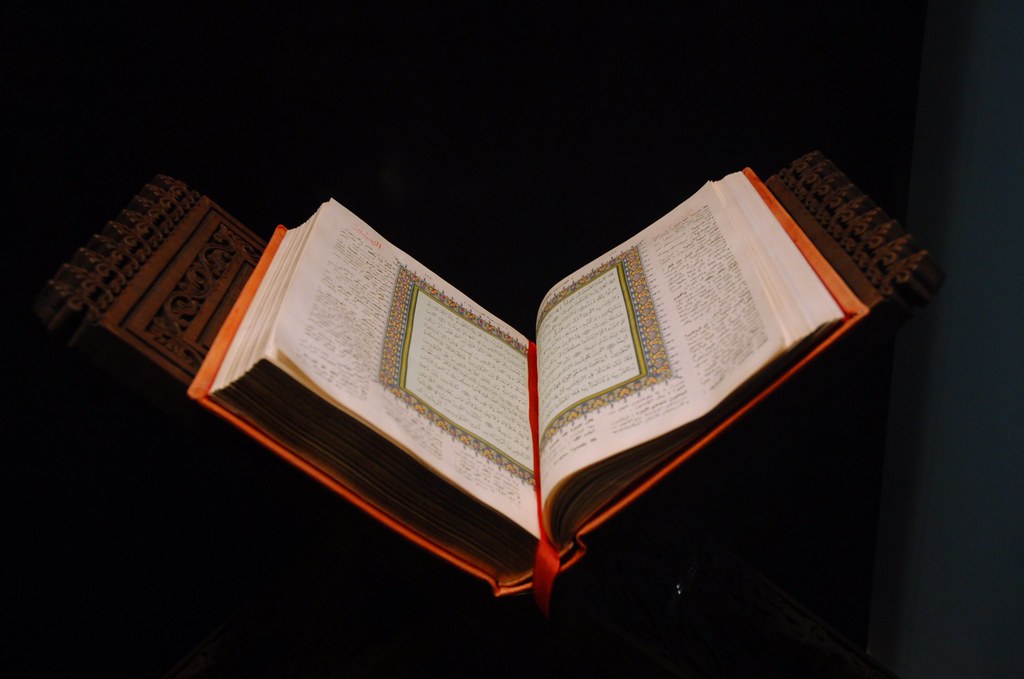

When it comes to Islam, though, the mood turns serious. The TV shuts off; the lights dim. We pray at length. We sit on the carpet, and my uncles sermonize, calling on their deep knowledge of scripture and Islamic scholarship.

Islam is infinite in its complexities, they say, but there are a few bedrock principles.

There is no god but Allah. Muhammad, His last prophet, delivered us the Quran as the final revelation. On the day of judgment, Allah will render verdicts for our souls.

As a kid I found little appeal in the doctrine. I did believe in a God of some sort. But there was so much certainty in their pronouncements. It didn’t sit well with my skeptical, questioning personality.

What I enjoyed was the sacred space with my family.

So I got smart, and I didn’t ask the wrong questions.

But a deeper issue festered. In college, I read about genocide in Sudan and an unjust war in Iraq. In my own world, in a big U.S. city, I spent a lot of time working in a local homeless community. I got to know people who had been cast onto the streets in large part because they were LGBTQ2+, HIV positive, or just poor.

On holidays I would travel to meet my family, and we would pray as usual. But it was getting harder to understand the relevance of the doctrine they were preaching – resisting Satan’s temptations, cleansing our souls for the Day of Judgement – to the world I saw.

What about this world? I thought. What about these people, here?

Years passed, and the flame of my belief dimmed, until one day it wasn’t there anymore. I figured I was just another disenchanted atheist.

Yet there was also this spiritual yearning that I couldn’t quite name. It showed itself on one bleak night.

My sister had a terrible accident and was wheeled into the ICU. The doctors made sure to set our expectations low. Sometimes they slipped up and referred to her in the past tense. Mom, Dad and I were near-hysterical. It felt like burning alive.

When our religious community heard, they came by the dozens. Just past midnight, one of my uncles called the group to prayer. They devoted Isha, the night prayer, to her.

Dad believes this is why she lived: Allah answered their prayers. I see it differently. But there was one thing I couldn’t dispute. In our darkest hour, in a moment of suffering, our community showed up to create a sacred space.

These days, I don’t think much about religion. I think in terms of spiritual need. Each of us, I think, feels a spiritual need, and we’re looking for a way to fulfill it.

Me? I’m not devout, and I’m not a convincing atheist, but one day I said, “I’m one confused-ass Muslim,” and I can’t tell you how good it felt.

I’m still spiritual, with my own mashed-up conception of spirituality. (Read Crossing Brooklyn Ferry and you’re in the neighborhood.) I try to keep it private, but what matters is that it’s centered on people, in the here and now, not the afterlife. And it’s about showing kindness to those who are suffering, as my community did that night in the ICU.

My wife thankfully remains my wife, and we have an understanding. When I’m with her, I’m the secular guy she’s always known. We hardly talk about spirituality or faith; our relationship functions well nevertheless.

When I’m around my family I am their good Muslim boy. When my nephews and nieces do something awesome, I say mash’Allah – what God has willed. When my uncles expound on this or that verse, I listen respectfully and try to find the lesson.

When my family gathers for prayer, it’s a sacred time for me. I stand shoulder-to-shoulder with people I love and respect.

I mouth the words Allahu akbar – God is greatest – and, in some convoluted way, I mean it.

Your friends at Preachy have decided to publish this essay anonymously, given concerns by the author that it might bring unwanted (and unnecessary) family strife.