Elon and the Flood

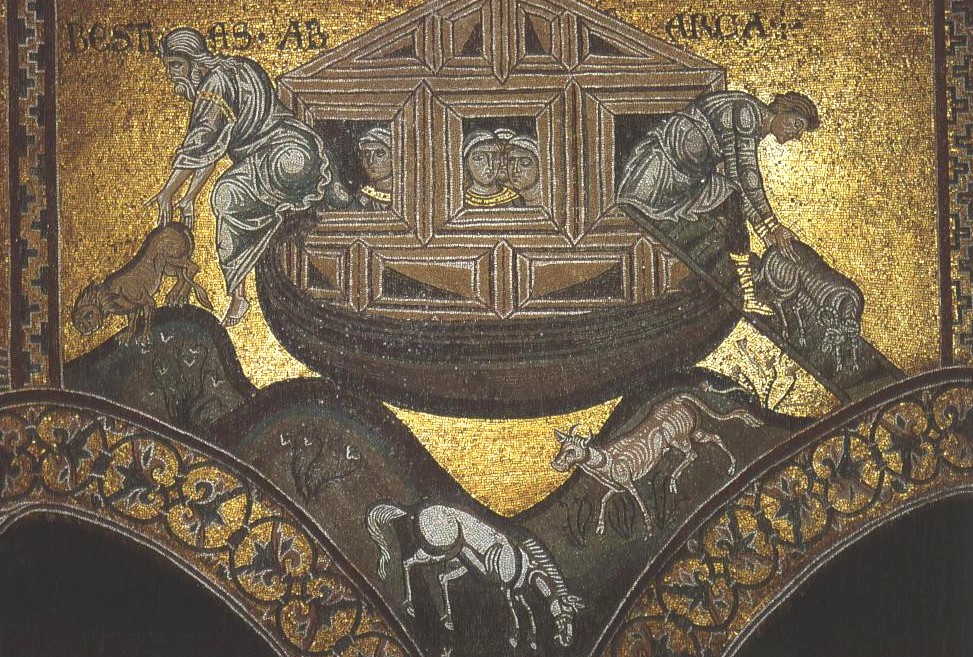

This spring, I took a Judaism class. I’m deeply interested in Jewish mourning rites, and the class seemed like a good way to get better acquainted with some of the rudiments of the religion. While there, I got a somewhat different take on Noah and the flood. As a girl raised in a Christian household in New England, Noah had been a cultural icon in Sunday school. Rainbows over a wooden ark, animals marching in two-by-two; Noah saves humanity. You might know the verses:

This spring, I took a Judaism class. I’m deeply interested in Jewish mourning rites, and the class seemed like a good way to get better acquainted with some of the rudiments of the religion. While there, I got a somewhat different take on Noah and the flood. As a girl raised in a Christian household in New England, Noah had been a cultural icon in Sunday school. Rainbows over a wooden ark, animals marching in two-by-two; Noah saves humanity. You might know the verses:

And the Lord said, I will destroy man whom I have created from the face of the earth; both man, and beast, and the creeping thing, and the fowls of the air; for it repenteth me that I have made them.

But Noah found grace in the eyes of the Lord.

My rabbi had a different interpretation: If Noah had 200 years, why didn’t he spread around a bit of his foresight and encourage his community to build their own arks? Why did he keep his knowledge of impending doom to himself (and his family)? Why didn’t he challenge God? In Judaism, Noah is not one of the cherished founding fathers, and with good reason: He does not argue, barter, or otherwise confront God in an effort to save his fellow citizens.

And maybe this is all about Noah rather than God. Maybe Noah wants to play his own hero role? Take a savior turn for the rest of humanity?

And that brings us to Elon Musk.

Musk, like Noah, believes that he is the sole savior of humanity. As the world’s richest person (a measure that would convince at least Joel Osteen and legions of U.S. Christians that he is indeed a chosen person), he is using his wealth to engage in a plan to “save” humanity from what he believes is inevitable destruction.

Also like Noah, Musk’s myopic view of survival discounts humanity. The world’s richest man has done little to help save, change, or improve the lives of the rest of the folks at his current terrestrial address. He has given less than .05 percent of his wealth to support any causes other than his own. And what he does give appears to be mostly in the interest of using his charitable foundations as tax havens.

Also like Noah, Musk’s solution to impending doom is a self-centered approach with enough room only for anyone with $500,000 in cash to pay for relocation to Mars. As such, his efforts here are specifically, proudly private and focused on wealthy citizens in wealthy countries. This, despite the fact that his projects have received hundreds of millions of dollars in public support. One could argue that, as such, this all goes beyond even Noah; by exempting himself from any popular will he elevates himself not just into a selector for the future of humanity, but into the very role the God played in the story of the flood.

To be clear: I’ve got no problem with colonizing space. Indeed, I believe that the more we work toward off-planet solutions, the greater our chances of long-term survival. But watching the one percent lift off for redder pastures while the rest of us choke on the industrial byproducts created by the mess that also bought them this particular ticket is just simply wrong.

When we — or our Gods — venerate human examples whose solution to saving humanity is nothing short of self-preservation, we are raising false prophets; we are choosing to iconize individuals who have no interest in the rest of us. Believing in heroes like Noah and Musk at the expense of humanity harms our collective chances of survival. Make no mistake: Musk is not our god. He is a billionaire building an ark, and in his scenario, he will choose who to save.